The Current State of the Opioid Crisis and Opioid Litigation

Introduction The United States of America is experiencing a widespread and prolonged crisis of opioid abuse, drug addiction and overdoses and death. Unlike other drug abuse crisis of the past, the opioid crisis knows no racial, socioeconomic, gender or age boundaries. It is claimed to have its genesis in the manufacture and distribution of legal but controlled pharmaceuticals that has spawned a wave of litigation against drug manufacturers, distributors, and pharmacies and in some cases individual shareholders, officers and executives of these companies. This paper will provide a brief introduction to the crisis, the current status of the litigations and address some issues regarding insurance coverage for the claims that are being addressed by American courts.

- What are Opioids

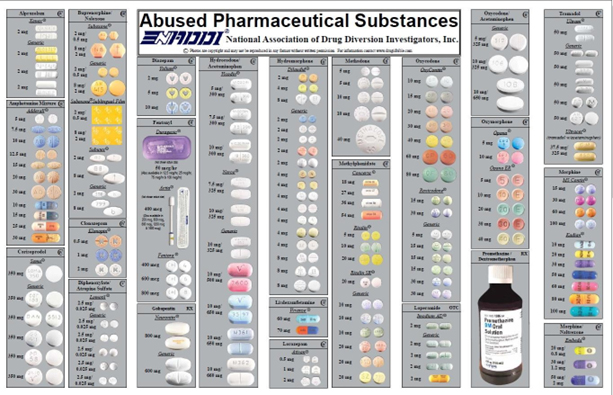

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describe opioids as “[n]atural or synthetic chemicals that interact with opioid receptors on nerve cells in the body and brain, and reduce the intensity of pain signals and feelings of pain.” (See Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Commonly Used Terms”, found at https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/ opioids/terms.html.) Opioids are a class of drugs that include many well-known prescription pain medications such as codeine, hydrocodone, morphine and oxycodone, as well as the illegal drug heroin and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl. Prescription opioids, or opioid analgesics, are used to treat moderate to severe pain. Opioids can be categorized as natural opioid analgesics (including morphine and codeine); semi-synthetic opioid analgesics (including oxycodone, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, and oxymorphone); or as synthetic opioid analgesics other than methadone (including tramadol and fentanyl).

Source: National Association of Drug Diversion Investigators, Inc., “Abused Pharmaceutical Substances”, 09/2018.

Opioid analgesics can also be classified according to the speed by which they are absorbed by the body and duration of their effects. The original opioid products were immediate-release opioids which were relatively faster-acting medications with a shorter duration of pain-relieving action. Extended-release/long-acting (ER/LA) opioids were developed in the 1990s, giving slower-acting effects with a longer duration of pain-relieving action.

Related to and an important part of the Opioid Crisis are certain non-medical opioids. Heroin is an illegal, highly addictive opioid drug processed from morphine a natural substance taken from the seed pod of the opium poppy plant. Methadone, the well-known treatment for heroin addiction, is a synthetic opioid. Similarly, there are legal and illegal varieties of fentanyl. Pharmaceutical fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opioid pain medication that is similar to morphine. A schedule II drug, it is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine and prescribed to treat patients with severe pain. However, illegally made fentanyl has become widely available in illegal drug markets due to its heroin-like effect and much higher potency, and it is often mixed with heroin and/or cocaine as a combination product. See id. CDCP. The combination of fentanyl with these other drugs is directly related to the increase in overdose deaths.

People have used products produced from the opium poppy for millennia. Opioids have been in use since the discovery of morphine in the early 1800’s. In the United States, through the 1980’s, opioid analgesics were largely used for treatment of severe pain, such as in patients suffering from malignant cancer. Concerns about addiction, as well as the limited duration and declining benefits of opioid products limited their medical use. Opioids developed in the 1990s were intended to act on a slower, more long-lasting basis to give relief to sufferers of less severe but nonetheless chronic pain, with a lower risk of abuse and addiction. Today, the CDCP still advises that “Opioid pain medications are generally safe when taken for a short time and as prescribed by a doctor, but because they produce euphoria in addition to pain relief, they can be misused.” (See id., CDCP).

The companies engaged in the manufacture, distribution and dispensing of opioids include many well-known American and international companies, such as Purdue Pharma, Cephalon, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Endo Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Insys

Therapeutics, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, Allergan (f/k/a Actavis), Watson Pharmaceuticals, Amerisourcebergen Corporation, Cardinal Health, Mckesson Corporation, Omnicare Distribution Center Masters Pharmaceutical, CVS Health Corporation, Walgreens, Rite Aid Corporation, and Costco.

- Development and Scope of Problem

Today’s Opioid Crisis is a problem that has been decades in the making. As the National Institute on Drug Abuse has explained,

“In the late 1990s, pharmaceutical companies reassured the medical community that patients would not become addicted to prescription opioid pain relievers, and healthcare providers began to prescribe them at greater rates. This subsequently led to widespread diversion and misuse of these medications before it became clear that these medications could indeed be highly addictive. Opioid overdose rates began to increase. In 2015, more than 33,000 Americans died as a result of an opioid overdose, including prescription opioids, heroin, and illicitly manufactured fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid. That same year, an estimated 2 million people in the United States suffered from substance use disorders related to prescription opioid pain relievers, and 591,000 suffered from a heroin use disorder (not mutually exclusive).”

(See National Institute on Drug Abuse, “Opioid Overdose Crisis – How did this happen?”, at <https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis>.) Recent statistics show that roughly 21 to 29 percent of patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain misuse them; between 8 and 12 percent develop an opioid use disorder; an estimated 4 to 6 percent who misuse prescription opioids transition to heroin; and about 80 percent of people who use heroin first misused prescription opioids. See National Institute on Drug Abuse, “Opioid Overdose Crisis – What do we know about the opioid crisis?”, at <https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugsabuse/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis>.

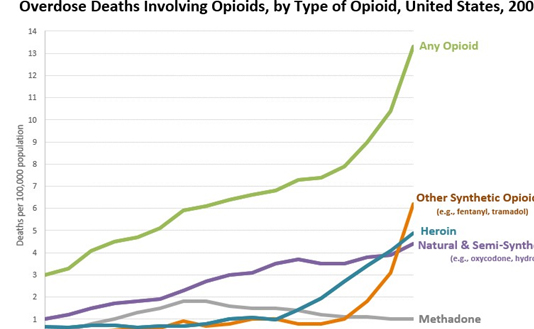

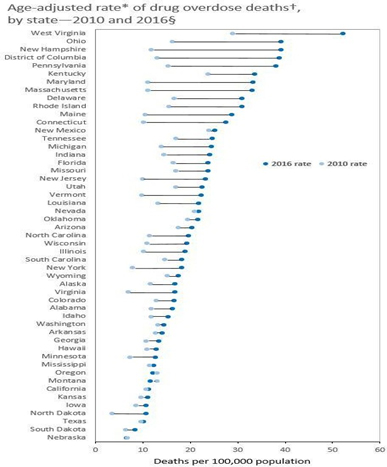

The CDC’s Annual Surveillance Report of Drug-Related Risks and Outcomes indicates that between 1999 and 2016, more than 630,000 people died from a drug overdose in the United States, but that the crisis has come in waves.

“The current epidemic of drug overdoses began in the 1990s with overdose deaths involving prescription opioids, driven by dramatic increases in prescribing of opioids for chronic pain. In 2010, rapid increases in overdose deaths invazolving heroin marked the second wave of opioid overdose deaths. The third wave began in 2013, when overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids, particularly those involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl, began to increase significantly. In addition to deaths, nonfatal overdoses from both prescription and illicit drugs are responsible for increasing emergency department visits and hospital admissions.”

Victims of this latest wave have included people in the public eye, such as actors Heath Ledger and Philip Seymour Hoffman, musicians Prince and Tom Petty, as well as thousands of ordinary Americans.

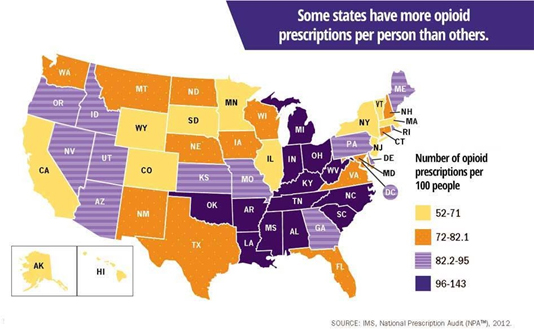

Although the Opioid Crisis is often associated in the popular imagination with rural populations in particular regions, such as Appalachia and New England, and states such as Ohio and West Virginia, it is truly a national problem. The National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that opioid overdoses increased 30 percent from July 2016 through September 2017 in 52 areas in 45 states. Opioid overdoses increased 70 percent from July 2016 through September 2017 in the Midwest. In large cities in 16 states, Opioid overdoses increased by 54 percent. Nationwide, the incidence of drug overdose deaths continues to rise, reaching a record number of 71,568 deaths in 2017.

The costs associated with the epidemic are enormous by any standard. The cost to health insurers is estimated to be $72 billion, annually. The President’s Council of Economic Advisors has calculated the cost of the crisis, in 2015 alone, to be $504,000,000. This number is comparable to the combined annual budgets of the states of California, Texas, New York and New Jersey in the same period.

- History of Liability Claims

The first claims and suits related to opiates were brought in the early 2000s against pharmaceutical manufacturers by or on behalf of individuals who claimed to have been harmed when they become addicted. Many of these actions were commenced in State courts and were dismissed or settled.

In addition, by the mid-2000s, numerous state and federal regulators had commenced proceedings or investigations against certain manufacturers. In 2007, Purdue Frederick Company, Inc. settled criminal and civil charges against it for misbranding Oxycontin and agreed to pay a criminal fine of $635,000,000. As part of the settlement, Purdue Frederick entered into a Corporate Integrity Agreement with the Office of the Inspector General of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, 26 states and the District of Columbia that required Purdue to ensure that its marketing was fair and accurate and to monitor and report on its compliance with the Agreement.

Beginning in 2014, numerous pharmaceutical manufacturers, distributors and retailers, including pharmacies, saw themselves named as defendants in actions commenced across the United States by States, counties, cities, towns and others, relating to opioid abuse and its effects.

In 2017, certain actions were transferred to the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, for consolidated or consolidated pre-trial proceedings in a Multi-District Litigation (“MDL”). Others have been subsequently transferred, and today there are over 1,100 actions pending in the MDL and in other state jurisdictions. At least 41 states have sued. Additional suits are filed almost weekly. President Trump has expressed his interest in the U.S. government bringing a similar suit of its own.

The Complaints assert various causes of action against the Manufacturer Defendants, including public nuisance, negligence per se, negligence, civil conspiracy, deceptive marketing, deceptive and unfair business practices, and violation of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Practices Act (“Civil RICO”). Many of the Complaints also include similar causes of action brought under State statutes. Some include causes of action designated as fraud and/or intentional misrepresentation. A small number of actions also assert claims against individual doctors accused of operating so-called “pill mills”.

The states, counties and municipalities in these actions seek injunctive relief and recovery of monetary damages for economic harm incurred due to various increased costs, such as costs for:

- providing medical and additional therapeutic care,prescription drug purchases;

- other treatments for patients suffering from opioid-related addiction or disease, including overdoses and deaths;

- costs for providing treatment, counseling and rehabilitation services;

- costs for providing treatment of infants born with opioid-related medical conditions and other child welfare needs;

- costs associated with law enforcement and public safety relating to the opioid epidemic; and

- costs for the loss of tax revenue.

The plaintiffs allege many types of wrongful conduct by the defendants that resulted in the plaintiffs’ damages. Typical allegations claim false and deceptive marketing of opioids by spending millions of dollars to sponsor purportedly neutral medical boards and foundations that educated doctors and set guidelines for the use of opioids in order to promote the liberal prescribing of opioids by making false and deceptive statements about the risks and benefits of opioids for treatment of chronic pain. Some complaints allege false and misleading claims, contrary to the language on their drugs’ labels, regarding the risks of using their drugs that: (1) downplayed the serious risk of addiction; (2) created and promoted the concept of “pseudo addiction” when signs of actual addiction began appearing and advocated that the signs of addiction should be treated with more opioids; (3) exaggerated the effectiveness of screening tools to prevent addiction; (4) claimed that opioid dependence and withdrawal are easily managed; (5) denied the risks of higher opioid dosages; and (6) exaggerated the effectiveness of “abuse-deterrent” opioid formulations to prevent abuse and addiction. Complaints also allege that defendants falsely touted the benefits of long-term opioid use, including the ability of opioids to improve patient’s function and quality of life, even though there was no scientifically reliable evidence to support the defendants’ claims.

- Current Status of Opioid Litigation

There are currently over 1100 opioid-related cases associated within the MDL styled In re National Prescription Opiate Litigation, which is assigned to United States District Judge Dan Polster of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, located in Cleveland, Ohio.

The MDL is proceeding in accordance with a Case Management Order (“CMO”) issued by Judge Polster in April 2018. CMO One established a case track system, whereby cases are, or will be, assigned to tracks within which discovery and motion practice will go forward as directed by the Court. Only one track was established by the Order. Track One includes three separate cases commenced in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio by The County of Summit, Ohio, The County of Cuyahoga, Ohio, and the City of Cleveland. The CMO sets for deadlines for discovery, depositions, and motions in Track One cases, and gives a tentative date for the beginning of a consolidated trial. The parties in the Track One cases will conduct written discovery and depositions pursuant to the Order. The Order also provides a briefing schedule for motions on threshold legal issues on common claims in certain cases the Court selected as representative. In their briefs, defendants seek to dismiss complaints, or selected claims. CMO One explicitly indicates that there will be coordination of the MDL with other State Court proceedings.

One key to the course of the litigation will be the use of a rich database maintained by the U.S. government that tracks sales of controlled substances (the “ARCOS database”). It is anticipated that this data will reveal whether companies neglected or ignored indications that their products were being abused.

There are at least another 200 State cases in other courts throughout the United States.

These non-MDL cases are pending in state courts including those in New York, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Connecticut and others. Certain state Attorneys General have commenced actions against some or all of the same defendants. In addition to various common law claims, the actions also assert claims under states’ unfair business practices and deceptive advertising statutes.

For example, in New York, twenty-three counties, the City of New York and the state’s Attorney General have commenced opioid-related actions. Plaintiffs filed a Master Long Form Complaint and Jury Demand (the “Master Complaint”) setting forth questions of fact and law common to all coordinated actions. The Master Complaint asserts 7 causes of action sounding in Deceptive Acts and Practices (NY GBL § 349); False Advertising (NY GBL § 350); Public Nuisance; Violation of New York Social Services Law; Fraud; Unjust Enrichment; and Negligence.

The MDL and non-MDL Opioid Litigations raise numerous legal issues, such as whether plaintiffs’ claims are preempted by federal law and regulation; whether claims are barred under the learned intermediary doctrine; whether the complaints meet standards for pleading fraud; whether statutes of limitations bar claims; and whether other doctrines bar or limit recovery.

- Limited Developments regarding insurance coverage for claims

Unsurprisingly, the claims giving rise to this opioid litigation have raised associated questions as to the defendants’ insurers’ obligations, as well. The limited number of decisions has addressed various issues, sometimes coming to conflicting conclusions.

- Do government claims seek damages because of bodily injury? Cincinnati Insurance Company, Plaintiff v. Richie Enterprises LLC, Defendant, 2014 WL 3513211 (W.D. Kentucky 2014) (no); Cincinnati Ins. Co. v. H.D. Smith, L.L.C., 829 F.3d 771 (7th Cir.2015) (yes).

- Do government claims seek damages arising from an “occurrence”? Liberty Mutual Fire

Ins. Co. v. JM Smith Corporation; Smith Drug Company Inc., 602 Fed. Appx. 115 (4th Cir. 2015) (yes); The Traveler’s Property Casualty Company of America et al., Plaintiffs and Respondents v. Actavis, Inc., et al., Defendants and Appellants, 16 Cal.App.5th 10226 (Cal. Ct.App. 2017) (yes).

- Do exclusions bar government claims? The Traveler’s Property Casualty Company of America et al. v. Anda, Inc., et al., 658 Fed.Appx. 955 (11th 2017); The Traveler’s Property Casualty Company of America et al., Plaintiffs and Respondents v. Actavis,Inc., et al., Defendants and Appellants, 16 Cal.App.5th 10226 (Cal. Ct.App. 2017) (Products exclusions).

In some cases, unanswered insurance coverage questions may be addressed using analogous decisions from prior pharmaceutical-related claims, or even other mass tort litigation, such as the epic Tobacco Litigation. Some coverage litigation regarding primary coverage for earlier phases of opioid-related litigation also exists, but it is yet to be determined whether and how such decisions may apply.

Conclusions and Remarks

The United States Opioid Crisis demands action but Opioid Litigation now pending in federal and state courts may give only some relief. Many ideas have been advanced for combatting the opioid epidemic. Some think new laws and regulations should put strict limits on the dosages of opioid prescriptions or length of time they can be used. Others suggest changing incentives and default practices in the medical establishment to curtail prescriptions in the first instance. Still others promote alternatives to pharmaceuticals for treating pain. However, none of these proposals can change the past or restore what has been lost.

Judge Polster recognized that the MDL is an imperfect approach to addressing a problem of enormous size and scope, stating:

I’ve handled and managed two other MDLs, and I’m familiar with many of the others that my colleagues have handled around the country. But this is not a traditional MDL. It generally focuses on something unfortunate that’s happened in the past, and figuring out how it happened, why it happened, who might be responsible, and what to do about it.

What’s happening in our country with the opioid crisis is present and ongoing. I did a little math. Since we’re losing more than 50,000 of our citizens every year, about 150 Americans are going to die today, just today, while we’re meeting.

And in my humble opinion, everyone shares some of the responsibility, and no one has done enough to abate it. That includes the manufacturers, the distributors, the pharmacies, the doctors, the federal government and state government, local governments, hospitals, third-party payors, and individuals. Just about everyone we’ve got on both sides of the equation in this case.

The federal court is probably the least likely branch of government to try and tackle this, but candidly, the other branches of government, federal and state, have punted. So it’s here. (Transcript of Proceedings In re National Prescription Opioid Litigation, Case No. 1:17-CV-2804, January 9, 2018.)

Americans, and the world, will watch the proceedings in Cleveland and in courts throughout the country, with great interest. However, it is unclear how resolution of the insurance claims and litigation will actually impact the continuing growth of addiction and social despair brought on by this crisis.